Freedom of Expression:

Washington, DC, USA

Rosemary Smith, author

Who do we want to regulate what we can say? The Government? Social Media Platforms? Extremists? In the United States, the First Amendment to the Constitution prevents government from making laws that prohibit free exercise of religion, freedom of speech, press, or the right to petition. It was adopted December 15, 1791 and has stood the test of time and the courts as one of the ten amendments that compose the Bill of Rights.

“Freedom of press, speech, and religion… any limitations on that freedom to express yourself is considered an anathema to that value,” says Jeffrey Gettleman, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist. “The first stages of tyrannical government are to limit what the press can say. Once the press is out of the way, they have an open door to corrupt regimes. It’s difficult to limit free speech in a fair way because cause you are then empowering some authority to decide what is good speech and what is bad.”

In 1949, the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) adopted the Fairness Doctrine. The policy required broadcasters to present controversial issues of public importance in a honest and balanced manner. The FCC eliminated the policy in 1987, removing the rule from the Federal Register in 2011. It had two essential elements requiring broadcasters to devote airtime to matters of public interest and then to air contrasting views about those matters. Its goal was to allow people to hear both sides of an argument, decide which aligns best with their values, then form educated opinions. The demise of this FCC rule is considered a contributing factor of rising polarization – politically, in communities, even in families. When broadcasters choose to report one side over another, consumers lose the benefit of half the valid information available. This issue leads to confirmation bias – where we get led down one side of an opinion based on the news sources we follow. The less we hear from the other side, the less we are likely to empathize or understand opposing views. This widens the perception gap, making us less capable of resolving disagreements or using check and balance systems to pass progressive legislation. Confirmation bias is one of the most polarizing elements since the advent of the internet. \

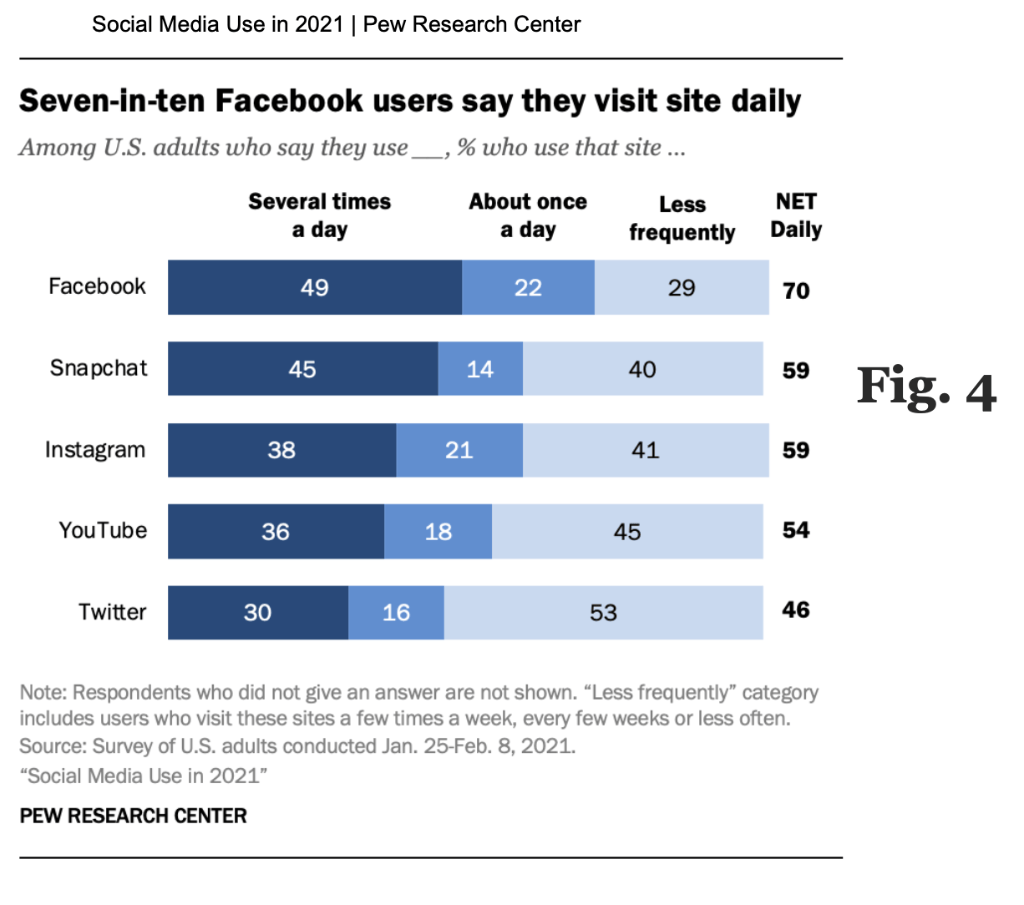

Thomas Jefferson said: “We can tolerate error as long as there’s freedom.” Of course, President Jefferson never used a mobile device or had access to hundreds of news sources at the tip of his fingertips, but he wasn’t averse to one-sided news reporting either. In 1791, he and James Madison helped found and even contributed political content to the democratic-republican National Gazette, in response to the Gazette – a more federalist paper. While potential “errors” or “fake-news” made in a 1700s newspaper may have influenced a semi-weekly reach of 1,400 people nationwide, today roughly seven in ten people are on some form of social media – according to PEW Research, that’s roughly four BILLION people.

So, when mis, dis, and mal-information is shared, the potential for it affecting millions of people become possible. Scenes like the one “Trust Me” captured in India of a mob forming and lynching innocent adolescents because of misinformation online become possible. Stories like “Pizzagate” where a North Carolina man took an assault rifle into a Washington DC pizzeria to free abused children supposedly held in the basement, become possible. Edgar Welch was misled by the story, which was circulated online, garnering shares from movie, athletic, and recording stars like Justin Bieber. Real people. Really, fooled.

Once people gain media literacy, they are less likely to be triggered by the vast amount of news media they are exposed to daily. They are more able to focus on their work, school, hobbies, relationships, family. They get more sleep. They become more resilient. They trust others more. When people trust one another, they tend to help one another more… see others’ perspectives. Progress is enabled.

“If men are to be precluded from offering their sentiments on a matter, which may involve the most serious and alarming consequences that can invite the consideration of mankind, reason is of no use to us; the freedom of speech may be taken away, and dumb and silent we may be led, like sheep, to the slaughter.” — George Washington, first U.S. president and founding father.

“Freedom of conscience, of education, or speech, of assembly are among the very fundamentals of democracy and all of them would be nullified should freedom of the press ever be successfully challenged.” – Franklin D. Roosevelt, 32nd U.S. president.

Are these founding thinkers and leaders in our democracy wrong? Should we ignore history – Nazi Germany, Pol Pot, Stalin, Leopold II, Kim Sung, Saddam Hussein, Idi Amin, Mao Zedong, and other tyrannical regimes who repressed people by limiting what they can say, what religion they can practice, their right to bear arms? Should freedom of expression be abolished now that we have technology leaders willing to sensor our speech through platforms they’ve created and profit from? Wouldn’t it be better if we learn how our words affect others, and choose to share them more wisely? Sounds a lot like media literacy.

“I now know what it feels like to be you” – Michael Shermer